Archive for April 17th, 2012|Daily archive page

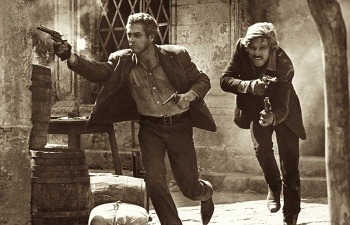

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid (1969)

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid

★★★★☆

Directed by: George Roy Hill

Written by: William Goldman

The well-deserved Oscar William Goldman received for writing Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid wouldn’t have amounted to much without the smooth, masculine chemistry between Paul Newman and Robert Redford, who sell the hell out of the roles. As an overall film, the movie is a bit measured for modern tastes, with the extended chase scene in the middle setting up a montage before skipping down to Bolivia where the third act unfolds. The subtle love triangle between Butch, Sundance and Etta Place is probably the second best part of the film, behind the cool and funny banter exchanged by the two principals.

Oddly, the thing that sits the most awkwardly, at least to my modern eyes and ears, is the Burt Bacharach score (which also won an oscar) and the 60s pop tunes that bubble and fizz over the top of the film. I guess the general cheesiness associated with “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” in 2012 may not have been so freely associated in the late 60s, but it (and the other syrupy scoring) glares like a bubblegum chewing beast of a child within the context of the stylish cool of the performances and cinematography. I guess it’s simply a part of the film and you have to take it as a package (after all, its not like musical atmosphere is a new development; movies have been scored with tonally appropriate background music for decades before and since) but for me it mars an otherwise excellent film.

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007)

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead

★★★★☆

Directed by: Sidney Lumet

Written by: Kelly Masterson

Let’s start off with the two fairly minor things that didn’t work very well for me in Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead. The first is the unnecessary POV-shifting, scene-revisiting, flash-back-and-forth construction of the film’s narrative. When a film like Pulp Fiction, which had lots of characters who all had individual arcs and criss-crossing story lines, fiddles with chronology, it makes sense because the narrative isn’t particularly linear or, more to the point, it isn’t as effective if told linearly. But in Before The Devil, there’s no point at which you can say, “If we already knew what was going on behind the scenes here, this would be less effective,” or “If we hadn’t gotten the other characters’ perspective on the scene with the current point of view character, we wouldn’t have as much empathy for what is happening.” The result then, is a gimmick. And there’s no need for a gimmick in a movie as riveting and powerful as this.

The second thing that didn’t work is Ethan Hawke. No disrespect to the actor, who does what he can, but I read that his character, Hank, was originally supposed to be a 19 year-old and was cast older to make him seem more tragic. Except it doesn’t make him seem more tragic, it makes him seem more unbelievable. Part of it is that the script, intending for Hank to be youthful, doesn’t ever have a chance to deal with the circumstances that might make a nearly forty year-old man into such a sniveling, un-worldly pantywaist. We’re just supposed to accept that Hank is this way but Hawke has too much soul in his eyes and too much natural presence in the world to sell the level of incapability he’s supposed to. Perhaps it was bad casting, perhaps Lumet just needed to leave the original script alone more, it’s hard to say.

But beyond this, we’re treated to a slow-motion train wreck of self-implosion and a study on causality that is gripping and delirious. The film follows Andy (played with an almost frightening amount of emotional range by the brilliant Philip Seymour Hoffman), an exec with demons to spare who comes up with a plan to help himself, his weak-willed brother Hank and his drifting/distant wife, Gina (played for the first half of the movie by Marisa Tomei’s breasts, then for the second half by Marisa Tomei’s bitten bottom lip). He concocts a victimless, nonviolent robbery of their parent’s jewelry store and tasks Hank with executing the plan. Through a series of sloppy preparations and sheer misfortune, the robbery goes bad and the impact of Andy’s plan sends shockwaves through their extended family. As things careen wildly out of control, the movie flips back and forth between Hank, Andy and their father Charles (played with mush-mouthed ardency by Albert Finney), showcasing the top down collapse of all three.

It’s a crime film that is more about family than glorifying lawlessness. It’s a movie that is, more than anything else, about the cost of decisions people make. These are not hardened criminals, they are desperate people who don’t seem to understand Newton’s Laws apply to human behavior as well as the natural world. It’s a family drama that plays out on a whole different scale than something more subtle, like perhaps Rachel Getting Married. Not that the two films are thematically alike at all, but the dissection of darker family secrets runs a connective thread between them and similar films, but where emotive dramas culminate in characters that rise above or grow beyond or simply take their leave, Before The Devil climaxes with the most complete depiction of a man pushed over the edge as I can recall seeing. Hoffman owns the last fifteen minutes of this movie, if he doesn’t own the entirety of it.

This is worth watching for his performance alone, and the rest of the movie is pretty good as well. I do wish they had made a couple of better decisions on the directorial end, but I can’t help but recommend watching, especially if you need to remind yourself that no matter how insane your family may be, it always could be worse.

Red State (2011)

Red State

Red State

★★★☆☆

Directed by: Kevin Smith

Written by: Kevin Smith

I decided to watch Red State after finishing Writer/Director Kevin Smith’s book, “Tough S—t.” It’s a bit difficult to know whether it would have been a different experience to see Red State without the contextual framework provided by the discussion in the book. And, to be honest, some of that is even dependent on the facts of my familiarity with Smith’s other work, because I was a big fan of Clerks, Mallrats, Chasing Amy and to an extent Dogma, but starting with Jay and Silent Bob Strike back, I haven’t been as adamant about following along with Smith. I did get around to seeing Clerks II and Zack And Miri Make A Porno, but unlike the previous films which I practically saw on opening weekends, they were grudging, not-in-the-new-releases rentals. I never did see Jersey Girl or Cop Out. And I probably wouldn’t have bothered with Red State either, except Smith, in his book, describes it as his homage to Quentin Tarantino. And, well, I sort of masochistically wanted to see what a Smith-does-Tarantino flick would look like.

But this is why I think if I didn’t know that’s what Smith was doing, I wouldn’t have had the same reaction. Because Red State is a very different kind of movie from anything else he’s done. Oh, sure, Dogma had its scenes of intense violence and religious themes, but it was still essentially Mallrats with a much grander concept. Gone are a lot of the aimless asides and the shock-schlocky, replaced instead by a script that is curiously focused while at the same time never quite being pinpoint. It’s never easy to tell who the protagonist is in the story, though the villain is sort of obvious, except that it is really circumstance that propels most of the deplorable actions, not all of which are done at the hands of the “bad guy.”

Let me give you an example of one of the many unusual decisions Smith makes in the construction of this film: Following the initial set up and the introduction of a few key characters, Smith films almost the entirety of a sermon, delivered by Abin Cooper (played with a pitched charisma by Michael Parks) that starts off as a genial, inviting, small-congregation fireside chat but slowly—almost laboriously—descends into a seething roil of hate and hellfire, culminating in an uncomfortably unflinching ritual murder. Smith describes in his book a desire to never take the obvious path with his story and this comes through as the winding narrative feints this way and that, suggesting at various stages a campy sex romp, a torture porn thriller, a straight up horror slasher, a cop siege procedural, a dark morality tale, a supernatural allegory and a political potboiler. It’s sort of all and none of those things.

What it definitely adds up to is a Tarantino-esque indie shootout talker. On that level, knowing that’s what Smith wanted, it succeeds. From a pure storytelling standpoint, Red State is gripping and unpredictable, which is what I liked most about it. On the other hand, Red State also struggles in its effort to be unexpected, to have a sense of purpose. It seems like it might be fairly obvious that Smith is demonizing hate-in-God’s-name publicity morons like the Westboro Baptist Church (or any other unpleasant organization using warped ideals to judge or detest others) but aside from a base despicable-ness to their convictions, the Five Points Church (led by Cooper) respond to the circumstances the film throws them into with a peculiarly understandable motive. The “good guys” of the ATF, led by Joseph Keenan (played with superb, nuanced inner conflict by John Goodman), are the ones who, though ostensibly in the right, often make the most unconscionable decisions.

Most of the neutral parties caught in the middle are never really given a place in the theme, which means they become expendable to the script. Smith tries to make a certain amount of sense of it in retrospect with an overly expository interview scene. To an extent I like this choice because it cements the fact that tense, adrenaline-fueled scenarios like this only ever have context after the fact, but the highlight passage from the script in this scene suggests that Smith’s moral is the same as he leveled in Dogma: be wary of faith without reason.

And then the part that ultimately dropped the film an entire star for me comes in the epilogue. Note, this is (I guess) spoiler territory, but understand that the linear construct of Red State isn’t really that important; in any case, you can skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want to know. Anyway, the final scene in the film is Cooper in prison, wearing an orange jumpsuit and singing a hymn in his cell. It’s a long, intentionally ponderous shot and then finally, just before the credits roll, someone off camera (presumably a fellow inmate) hollers, “Shut the f—k up!” My problem with this is that it seems to be a semi-symbolic part of Smith’s message, hinting strongly that what he really has to say to misguided faith-based lunatics is “just go away.” I have a big problem with a film that is as thoughtful as Red State going for either a laugh or a frustrated outburst or both as its closing statement, especially coming from a guy who has made a career out of being overly honest, whether that’s with his character mouthpieces in his films or his podcasts or his spoken word public speaking or his book. It’s so simplistic and glib and counter-productive to summarize an issue like reconciling the troublesome nature of deplorable ideas that are so easily translated into antisocial actions with a simple gag order, even played for (non) laughs. The film, sadly, would have been at least 20% better without this final, 30-60 second scene.

All told, Red State is a promising new direction for Smith. Unfortunately, if you believe what he says in his Tough S—t book, it will be his penultimate film. Smith has been uneven as a filmmaker, even from the start, often accidentally achieving greatness. Here, he accidentally misses greatness and showcases a potential for something grittier and different from what others might say with similar material. And that’s exactly what you want from a filmmaker, I think.