Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Blog Archives

iloveoldmagazines: Holiday April 1961 via survival2019

Just discovered Koren Shadmi. Great stuff.

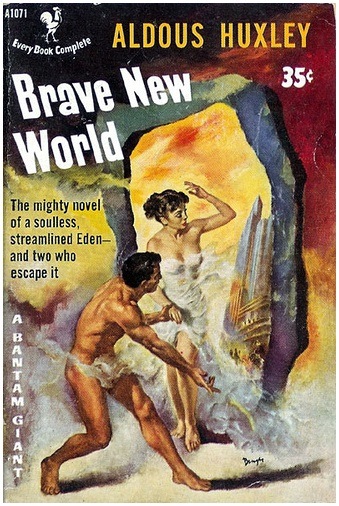

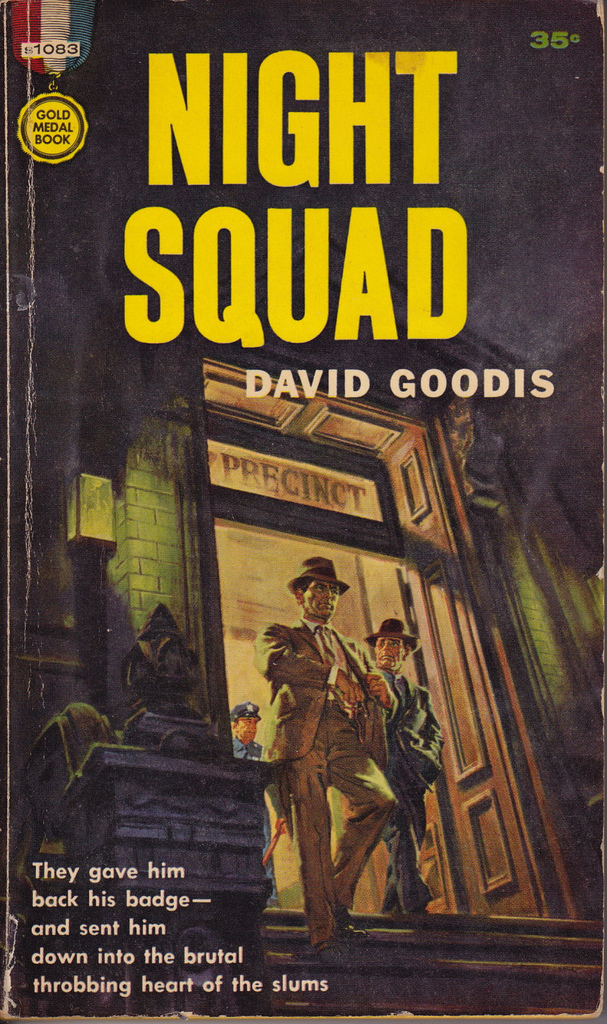

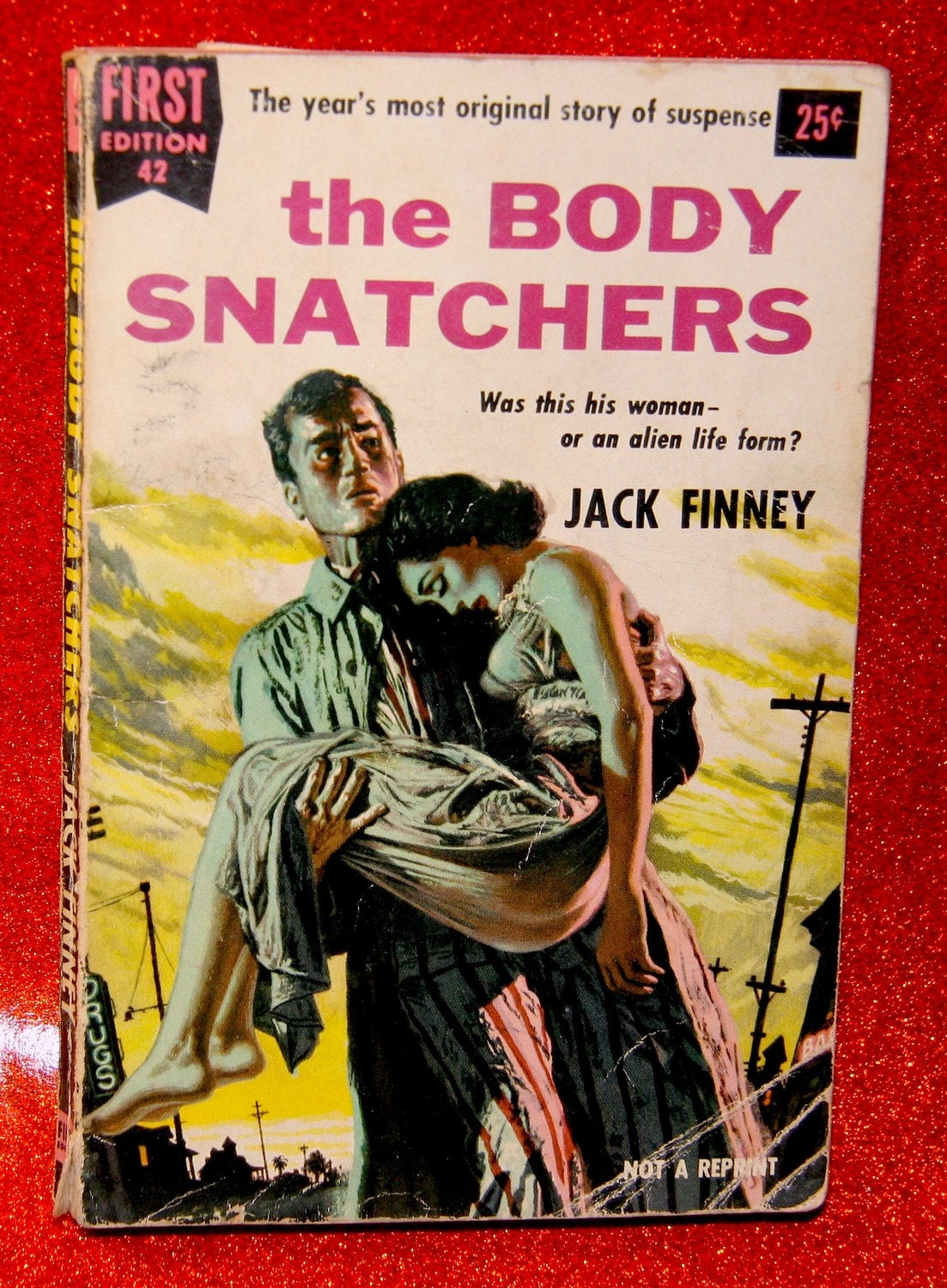

Pulp Covers

Stylistically, I love pulp cover art. The association with exploitative imagery is perhaps somewhat regrettable, but the rough, half-comic book, half-painterly feel of the type is so vibrant and evokative to me. If I ever have a novel published I think I’ll do whatever I can to ensure that the style is applied to my book jacket.

#

The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William…

The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William Joyce and Brandon Oldenburg.

Hauntingly sweet.

#

bookshelfporn: Library Rocking Chair Nice design, except I…

Library Rocking Chair

Nice design, except I feel like I’d be too short to reach the books on the top shelves.

#

The Kite Runner

author: Khaled Hosseini

name: Paul

average rating: 4.15

book published: 1385

rating: 3

read at: 2011/12/04

date added: 2012/01/23

shelves: novel

review:

You know those commercials for the SPCA that have Sarah McLachlan’s “Angel” playing and a slide show of abused and pitiful looking dogs and cats? Everyone I know hates those commercials, and with good reason. They’re manipulative, playing your emotions without any real motive aside from gain. It isn’t that they aren’t effective, it’s that they’re so transparent in their subtlety-deprived excavation of our knee-jerk emotional response that you hate them for being so good at what they’re clearly trying to do, in part because they don’t earn it. We have this sense that we should not be moved to tears by a thirty second commercial, so when we are because of some laser-targeted heartstring yanks, we don’t admire the efficiency of the effort, we just feel resentful and call it cheap.

I bring it up because I felt that way a lot when reading Khaled Hosseini‘s The Kite Runner, like I was being played somehow. Like those loathed commercials, it wasn’t that the book was ineffective, it was that it felt like it hadn’t really earned its response from me. Admittedly, this is an awkward criticism to level at a novel. What counts as effective and well-deserved emotional investment? It’s as subjective as opinions on the quality of writing itself. Ahem.

But I think it starts with realistically crafted characters who are more than puppets, who inspire affection and sympathy from readers in the same way real people do, by having faults and overcoming obstacles and being relatable. Too many of the characters in The Kite Runner seem to exist in such a compartmentalized way as to serve only a single possible purpose. The biggest example of this is the unbelievably saintly Hassan, our narrator’s sort of half servant, half friend. In order for the protagonist to have a crisis, he must sacrifice Hassan and his innocence (a symbolism effort that is precisely as restrained as those bloodied puppies from the SPCA spots) and while the sequence is, truly, harrowing and effective, it feels sleazy and conniving as well. I’m not even sure what to contrast this to, because it seems like so few other authors would dare to stoop to the level of brutalizing a saccharine character in this way just to introduce some conflict. Those aren’t puppet strings Hosseini grasps, they’re puppet bridge cables.

The story is of Amir, the narrator/protagonist, a boy growing up in Afghanistan just before the Russian invasion in the late 1970s who emigrates to the United States as a teenager to escape the conflict. The first third or so of the book deals with his relationship to Hassan, the turbulent quest for approval from his father, Baba, and the encounter that drives a wedge into all of their lives. The second part of the book is the by-the-numbers coming of age bit, set in California. In fact, it is set in my hometown.

Let me pause here for a second and talk about this setting and the way Hosseini deals with it. Admittedly, part of the reason I even picked this book up was because of its Fremont, CA secondary setting. I know this is extraordinarily nit-picky but it annoyed me an awful lot that some of the details which are thrown in about the town are exceptionally strange ones. Not so much that they are completely incorrect or indicative of heavy license being taken with the place—I actually wouldn’t mind so much if the Fremont depicted here was sort of a fanciful version of the town I once knew more intimately than any other on Earth. The problem is that he includes really random tidbits that just feel as if they were constructed without any real research or any true local’s appreciation for what the place is actually like. For example, at one point he talks about the Indian movie theater and, contextually, I assume he’s referring to the Naz cinema which was, at one time, located in Fremont’s Centerville district. But the time setting here is the early 1980s and I happen to know that the Naz took over a building that used to be called ABC Theater which showed second run movies, double features and Rocky Horror on Saturday nights up until 1988 when it sadly went out of business. It wasn’t until the early 90s that it became the Naz, which from what I can tell was the first Indian theater in the area. You can see how someone who came to Fremont after the Naz was in place would assume it had been around for a long time (it’s a very old fashioned looking theater) and had always shown Indian movies. A bit of research could have cleared it up. Other nagging details annoyed as well: At one point he describes mapping out a route to hit up the best garage sales on a Saturday and listing the East Bay towns but in a totally nonsensical order: “Fremont, Union City, Newark, Hayward.” Any East Bay resident will tell you that with Newark being southwest of Fremont and Union City being northeast with Hayward beyond that, you would never hit up Newark in the middle of a trip to UC/Hayward. Never. It’s backtracking twice. It’s stupid. He goes on: “San Jose, Milpitas, Sunnyvale, and Campbell if time permitted.” No. You have to drive through Milpitas to get to any of those other three South Bay towns and if you hit Campbell last, you are at the furthest southern point from home. And yeah, I know he doesn’t necessarily say that was the order they visited the towns in, but I don’t know anyone who would list a number of cities they visited in a random order that way. It’s like saying, “I went to Las Vegas, Detroit, Phoenix, and then Chicago by train.” It sounds awkward if you know anything about geography.

At any rate, the third section of the book is devoted to Amir’s return to Afghanistan, drawn back by an opportunity for redemption offered by one of Baba’s close friends who stayed behind. And if the first section of the book feels manipulative and undeservedly touching, Hosseini wastes no opportunity to exploit emotional triggers or thrust new pictures of abused innocence in readers’ faces. In a lot of ways the book feels like every Hollywood tearjerker cliché packed into one unbroken string of groan-inducing pile-on. The tortured artist hero; the journey-quest for redemption; the family secret unveiled; the surprise return of the villain; the one-last-mistake climax; the bleak ending with the slight nod toward hope; it’s all here.

In the end, I resent The Kite Runner. I resent it because Hosseini is not ineffective with his crude use of these simple tools and I resent it because the book is written in a way that makes it easy to swallow if difficult to digest. I resent it most for being so blatant and unsophisticated while having the audacity to be somewhat effective. The novel hits a lot of my downgrade triggers—apart from this cheap, Oprah-book sensibility—too: A writer protagonist (when oh when will writers look past their own self-important noses for pity’s sake?), an in-prose discussion of the prose itself (the section about endings toward the end is like one big “don’t blame me if you’re disappointed in a few pages” caveat), book-club-ready dream sequence symbolism and excessive bookending (the “oh, look what I dregged up from the first twenty pages in the last twenty pages” syndrome).

But what I resent most about The Kite Runner is that I couldn’t bring myself for whatever stupid and sentimental reason to outright hate it. As much as the book annoyed me—incessantly, endlessly—throughout reading it, I found the experience to be a sickening seesaw between my brain and my heart. All the while my cynicism and critical thought processes were deriding the book and its crass, obvious machinations, my manipulated emotion centers were loving the characters of Baba and Soraya and Hassan and Sohrab, desperate to find out what happens to them all. I flipped back and forth between wanting to toss the book aside in snooty disdain and finding myself unable to stop reading it until I reached the end. I hate that I could see so easily through Hosseini’s book and yet I fell for it completely.

Like a person who has to donate to the animal shelters because Sarah McLachlan and the sad-eyed kittens gave them no choice, I may not feel good for being so regrettably lacking in control for my own response and actions, but I can’t deny what they were. The result is a book I will never recommend to anyone but which I must begrudgingly admit I devoured.

Great Stories by Chekhov

author: Anton Chekhov

name: Paul

average rating: 2.00

book published: 1966

rating: 2

read at: 2011/11/29

date added: 2011/11/29

shelves: short-stories, classic

review:

Classic literature, especially classic Russian literature, vexes me. I know roughly nothing about the Russian language so I sometimes console myself as I struggle with Dostoevsky or Tolstoy (which I’ve occasionally attempted but never fully conquered) with the notion that written Russian is particularly difficult to translate into smooth reading English. But then again, I get this way about classic English lit sometimes as well, where I see words on the page and just can’t seem to get through them into that fugue state where I’m not really reading as a mechanical word-eye-brain-context-thought-idea process, but as a sort of direct input from the author’s imagination, utterly unaware of the printing or the sentence construction; it’s like drawing ideas from the page via some kind of mind vacuum.

I guess there is a reason why I’m not an English major (or any kind of major for that matter). Chalk me up as just another filthy soul populating the unwashed masses.

But I like stories. I love books and written words and I have enjoyed some classics, even some stuffy and difficult works, both modern and time-honored. So I don’t always know what it is that may cause me to go cross-eyed with frustrated agitation that a story just won’t seem to let me in.

So consider my first foray into Anton Chekhov. On one hand, there are moments in the fairly limited collection of Chekhov’s work included in this old paperback printing I found for a song at a used bookstore which reveal clearly why he is considered a master of the short form. “The Kiss,” for example, an early inclusion about a lonely young soldier who happens upon a stolen moment of intimacy, intended for someone else entirely, and uses that off-handed experience to construct for himself an entirely new persona, a boosted ego of imagination and possibility which has, in spite of the joy it brings him, a tragic collision with the reality of, well, reality. Another pair of tales, “A Father” and “A Problem,” highlight a certain astonishing insight into human nature, simply revealing complex elements to relationships in a relatable way.

But then you get to some of the longer works included here, such as “Ward No. 6,” and I start to hang back on the dry exposition, the deliberate pace to a character study that, too, has something interesting to say but says it in such a dull fashion that I struggled to get through the 30-some page short over the course of about four days. Again I found myself looking back on my own Russian lit crutch and saying, “Well, maybe it’s just the translation?” But maybe it isn’t. At least in the case of Chekhov, or perhaps in the case of this particular collection, the longer the story gets the harder it was for me to muddle through. I like the way I can see his mind working: his philosophy and his understanding of what makes a character interesting combined with a detailed sense of realistic arc make for living souls in the stories but at some point it’s like reading 500 pages about a grandmother spending an evening watching TV: no matter how good the writing is, the subject is bound to wear out its welcome if you linger too long.

I couldn’t help contrast this selection with the Raymond Carver volume, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love that I read earlier in the year. Carver’s direct-to-the-point simplicity doesn’t need fantastical things to happen to be compelling. The slice of life examinations are reminiscent to Chekhov’s, in spite of being separated by nearly one hundred years and half a planet. But Carver (or his editor) never let those tales overstay their welcome, stripping them down to their barest necessities leaving only that which absolutely must be revealed. They both traffic in sadness and irony and the bitter pill that is life, but where I could not put down What We Talk About, I couldn’t wait to set down Great Stories. I can attribute this fact to the editors, to the translators, to the authors or to myself but in any case, what I cannot escape is that I didn’t much care for enough of this book to recommend it or even like it. At best I can say it was okay and I’m intrigued to know more about the author’s work, but when I dive in again, I’ll be sure to be more selective about which volume I choose and not let a bargain make my decision for me.

One for the Money (Stephanie Plum, #1)

author: Janet Evanovich

name: Paul

average rating: 3.80

book published: 1994

rating: 3

read at: 2011/11/17

date added: 2011/11/24

shelves: mystery, novel

review:

Stephanie Plum is, at first blush, kind of a cookie-cutter feisty heroine, the kind who appear in mystery novels and television shows often as the kind of safe pushback against the damsel-in-distress archetype. But the thing Janet Evanovich does that I like is she starts her series with Plum green and soft, just getting into the boys club that other authors would have their protagonists waltzing through as old hands. It is this trial-by-fire atmosphere where readers share in Stephanie’s alternately terrifying and hilarious mishaps as well as her triumphs, both minor and major, that make her an interesting character.

One For The Money follows the down-and-out Stephanie Plum as she finds herself six months out of a job, selling off her last few possessions to pay her bills and running out of options. In a moment of desperation she goes to her cousin, Vinnie the bail bondsman, looking for work. All he has to offer her is a longshot job as a bounty hunter, dragging in bail jumpers. She accepts, at first not sure at all what she’s getting into, and then she realizes her first target is a cop by the name of Joe Morelli, a heartbreaker from her neighborhood she has a short if rather checkered past with. Before she knows it, Stephanie is neck deep in the murder case against Morelli where it appears he killed an unarmed man. Mixed up in the whole deal is a sinister prize fighter who locks his eyes on Plum, another bondsman who goes by the name of Ranger, and a couple of plus-sized hookers.

Evanovich grants Plum’s first-person account of her inaugural stint as a bounty hunter a solid dose of humor, sass, humility, honesty and thrills to make for a race of a read. Plum feels authentic, going from adrenalized self-satisfaction to terrified near-victim regularly and offering plenty of plausible explanations as to why she doesn’t give up, revealing herself to be tenacious and endearing without being moronic. Moreover, the assorted cast of characters are perhaps not as well-realized but just as relatable and the interactions between the principals all feels genuine.

As a mystery, One For The Money is pretty good, although it isn’t difficult to tell which tidbits of information are important to the end sequence well in advance, at least the specifics of the plot aren’t readily obvious. Evanovich strikes the right balance between levity and gravity, ratcheting up the tension and the stakes through the course of the briskly moving novel until it gets pretty real by the end, but fortunately only in that sort of surface-level, Hollywood type of heft. What this does is make the book feel very escapist which is a positive thing, but it also makes it feel kind of lightweight and frivolous as well, which is perhaps not so good, depending on your disposition. This is a tough line to walk for mysteries: Too dark and you end up with Thomas Harris or John Sandford; too light and you end up with Nancy Drew. For the most part this beach-read vibe works in Evanovich’s favor, but I wonder if this kind of disposable sensibility can persist through a whole series?

All said, I enjoyed One For The Money quite a bit, and a lot more than I expected to. I’d pick up the next book in the series without hesitation and while it certainly isn’t going to be on any must-read list or be something I press on all my friends to read, the sort of lovable disaster that is Stephanie Plum is a character I’d be happy to revisit when I’m looking for another fun read.

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

author: Stephen King

name: Paul

average rating: 4.14

book published: 2000

rating: 4

read at: 2011/11/19

date added: 2011/11/20

shelves: memoir, non-fiction, writing

review:

The appeal of Stephen King, I think, has always been that he has a kind of everyman style which allows his work to be relatable, so he starts describing you or people you know and then his warped imagination kicks in and the effects are visceral and emotional. Often King uses this to punch you in the gut with cold fear, where other popular-but-critically-disdained authors might go for a well-timed weep (Nicholas Sparks) or maybe a coordinated sigh of relief (John Grisham).

One gets the sense from On Writing that King is a little bitter the literary community has crammed him into a box labeled “popular but trashy.” Its hard to feel too sorry for a guy who can presumably console himself by swimming Scrooge McDuck-style in his swimming pool filled with money, but in reading On Writing you start to understand that the reason King never made it into that snobby group of anti-taste, pro-pretense folk is because he doesn’t really care much about anything as high-falutin’ as art or pushing the boundaries of the novel format or challenging preconceptions of what a novel can be. He’s a storyteller. Someone, somewhere seems to have decided that the literary equivalent of telling ghost stories around the campfire is lowbrow and while you can tell it rubs him the wrong way, King finally seems to decide the problem is with the critics, not with him or his legions of fans.

I like King’s approach to writing. His advice makes sense to me, although he seems to be in favor of flying by the seat of your pants, finding that sketchy-to-describe place where the characters seem to take on their own lives and end up acting of their own accord. King comes as close as anyone I’ve seen to describing how this takes place, but even then, he can’t quite get over the big cloud-like shape on the blackboard labeled with “HERE BE DRAGONS.” It’s just too much like magic to try and describe how something that a person logically ought to control (it’s coming from your own mind for pity’s sake) in fact seems to be coming from somewhere else.

He advocates that the key to being a writer is to read a lot and write a lot. Makes sense to me. He has a few pieces of practical advice, too, although he doesn’t dive very deep into specific mechanics other than to recommend actually reading Strunk & White, avoiding adverbs and making rewrites 10% shorter than the first drafts. A lot of the rest of his advice is about process and this advice is the kind that I don’t know I’ve seen in other places. You can find plenty of other people who tell you to avoid adverbs and be merciless with rewrites but I haven’t encountered anyone who suggests keeping the first draft to yourself and getting help only once the whole story is written (King uses the metaphor excavated). I’m not sure anyone else would bother explaining why you should scoot your writing desk off into the corner of a room (though make sure the room has a door) instead of creating a monument to writing with some huge behemoth as a writing-room centerpiece. The best part, to me, of On Writing is the way King describes the Ideal Reader better than I ever could (and I have tried).

I can’t be sure if On Writing would appeal to anyone who didn’t have aspirations of writing. I think if you aren’t a writer and have no real desire to be, but you live with or know a writer, it might be interesting to get some insight on the kinds of things they might find fascinating and useful, but the only other people I can see really caring about this book are people really interested in Stephen King as a person. An awful lot of On Writing is the story of Stephen King, truth be told. It’s not, perhaps, a “proper” memoir, but because King is mostly known just for writing, it’s maybe as close as one might come. The first third of the book is a series of anecdotes and memory snapshots (entertainingly) told in King’s casual and readable style most of which serve to kind of explain how King got to be a writer and what circumstances lead to his stock and trade being a storyteller. Most of the rest of the book is the section about the actual act of writing and then the last maybe 15% is an odd sidenote about the accident he suffered in the late 90s, getting struck by a van. It does kind of come full circle as a sort of writing parable, but it feels like an odd inclusion here, in a way.

I really liked On Writing. I don’t even say that with a shuffle of my feet and a half-apology in my voice, either. I actually kind of expected to like it and I very much did. I think its practical information may not be applicable to every writer, but it felt applicable to me, and I hope it will make my writing better. The pseudo-autobiographical parts at the beginning were fun to read and interesting, also they were inspiring and able to show how tenacity is possibly the writer’s primary tool for success. And it’s a blisteringly fast read, too. I’m no speed-reader but I tore through this book in under five hours. I can’t be sure about the broad audience appeal, but I can say that if you have any inclination toward writing at all, at least give it a shot. You could even probably skip the third part where he talks about getting run over. Spoiler alert: he starts writing again. But even with this strange postscript, there’s enough here to make it well worth the quick read.